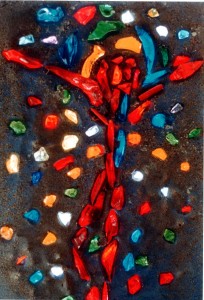

82 [28.] ‘Crucifix/Resurrection/Ascension’

Stained glass window. Colored glass chunks set in epoxy. 1′ x 2′ 1977Since the divine character is singular though dynamic, according to Catholic orthodoxy, the title and image above reflect three events, one Reality.

Since the divine character is singular though dynamic, according to Catholic orthodoxy, the title and image above reflect three events, one Reality.

This was a ‘study’ or test for a larger window that was accidentally destroyed subsequent to completion and the ‘test’ has also disappeared!

CHAPTER 4

In which:

-An apology about the text getting too personal is made.

-Some comments about Abstract Art are made.

-Monastic themes are presented.

-Icons

-Disaster in the monastery.

-Pilgrimage again.

-Religion and Art conflict, two examples.

-Great Old Man

-Pilgrimage and discernment of vocation?

-Art, Culture; prescience of a Tantric mural of the Resurrection.

-Seminary?

Bishop, excuse these following diversions. They are too personal. (Perhaps this whole Letter is too personal…) Though the exploration of “self” is the field of study for much of this work, it will usually be much less autobiographical. But I thought this significant catalyst to the turns and twists of this story.

One such twist of importance at this time is my paintings and what I believe is their abstract-expressionist, Iconic, Shamanistic power to catalyze events. During my last year of college, I made a breakthrough with my paintings. I started painting professionally good paintings. It was a series of spiritually animated “interior” landscapes wherein the action of the work was all drawn, pulled towards a distant luminous point on a vague horizon. One of the art professors in our department, a famous abstract expressionist, and a fine teacher, had plagued and harassed me for the previous two years because he just didn’t like my approach to making art. When I started painting these works, he watched me for a while, then apologized for his harassment. (He had once purposefully stepped on one of my drawings.) “I didn’t understand what you were working on.” These paintings were the first interior breakthroughs that evidenced personally, ontological changes necessary for me to make this journey. (See Visual Arts above, Before Bolivia,” #s -1 thru -5)

As I think back on what drew me to the monastery, there is one image, of a monk, that was in my mind’s eye during the later years of college. I was curious about the monk’s life even then. My first completed painting started out as one thing and became a very abstract image of a pilgrim monk climbing a mountain bent beneath a heavy pack on his back. This was just before the first quest or any pilgrimage. The shape of the burden slightly suggested the form of male genitals. Four years later, I completed my first series of professionally competent paintings mentioned above. Then began the First Series included here that are so important to the progress of this story. These were amorphic space and color with colorful hard edge or geometric developments that discussed symbolically the relationship between a general context, the “absolute,” in a counterpoint conversation with the specifics of our experience. These paintings follow through from Surrealist and Abstract Expressionist, Color Field painting to a phenomena quite different from the more popular Post-Modernist themes. I hope this will be clear by the end. This formal complex was a representational abstraction of feelings, thoughts, and perceptions that continued to characterize much of my work for several years.

In the monastery, I was hit by the impact of Icons. These are not mere illustrations, propaganda for the Church’s message. These are vehicles for the experience of God. I spent several years trying to integrate these two influences; Surrealist, Abstract Expressionism and the Theology of Icon. (See Ph.D. appendices Re: “Art” for evaluation of icons, mandalas and shamanistic fetish objects of power.)

In 1975, I was taught by a Chinese monk in the monastery whose father had become a Buddhist hermit in his later years. My teacher had been sent to study in Europe by his family in order to avoid his becoming a monk like his father. He converted to Catholicism and became a Benedictine monk in Belgium. He earned a Ph.D. in Diplomacy (Political Science) at Louvain, in Belgium. Then he was sent to China as a missionary monk. He helped found this California monastery (where I began my formal religious intiation) after the Communists expelled such Christians from China. We met in 1974 when I arrived at the monastery. He taught me a Catholic Catechism, monastic history, and Chinese brush painting. He baptized me the following year on the Feast of the Triumph of the Cross. It was a wonderful initiation- deep, practical and nuanced.

A few months later I was asked to leave the monastery. I had told the superior, who was a psychologist, that I was confused about my sexuality. He said to me that it was common. It is my belief that I subsequently offended the man because (as I was told years later), by the time the story was related to the Council of Seniors in the monastery, it got translated into my being active in the Gay world of Los Angeles. This is not true. I left amid much confusion and controversy. This was the first confrontation between my own confused dysfunction and that of the Church–a dialogue which develops in an interesting and perhaps salvific way. (It causes me no pleasure, that this superior was 15 years later to experience something similar as he had worked in my life. A woman accused him of performing sexual rituals on her naked body during psychological therapy sessions. By then, perhaps, this man, this monk, was burnt out by duties of too many years as superior of that monastery. He withdrew to a completely silent and isolated monastery after the eruption of that controversy.)

However, because of the checks and balances in these ancient institutions, this seemingly unfortunate and painful event was mitigated by the kindness of those who didn’t agree with this decision. Eventually, they, as well as that superior, helped me with other advancements, including entrance into the seminary. The psychological screening tests used by that institution showed that my personality would be better suited by the seminary and diocesan priesthood. My sexuality did not appear to be a problematic sort.

In the mean time, I spent time in retreat at a Trappist monastery and then in a Camaldolese hermitage. Besides still being impressed by the life style and the wonderful people in it, I had these experiences that characterize what happened to me there. In one of the monasteries, there was a young novice that stood in front of me in choir. When he first came there he seemed well adjusted and enthusiastic about monastic life. But something came to the surface over the following months: He started doing extra penances; eating less and less; trying to do more and more manual labor, which he didn’t do very well. He was doing more than the already hard rule required; superficial things, like shaving his head too often and too short so that I could see the bloody nicks in his skin as I stood behind him in choir. He tried to sleep less and less; study more and more. He wanted to become holy the first year of his life in the monastery. Too fast. These changes of life take a long time. Years. Such transformation is what these venerable life styles say life is for. Anyway, early one morning, after the 2:00 a.m. prayers, I heard terrible screams tearing through the otherwise silent monastery. This young novice had gone mad, attacking any monks he came across and screaming wildly. He was to be taken to the city hospital in a straight jacket.

Another time, I was walking in the fields- punctuated staccato with the dry stubble of the late fall, frost and ice crunching beneath my boots. It is pre-dawn twilight, a variety of fragile blues give way to warmer rose and yellow above the dark hills. On the far side of the field is a herd of elk. They graze, watch–suddenly see me. They begin to run. They flow as one body over the hills. Over the fences, easily. I watch and regret that they were running away. Delighted to see them at all, in awe to see them run like that. Such perfect wonder. I left the fields. Went to the chapel for morning meditation. Sensed even greater wonder in the Blessed Sacrament. It made even the largess and natural reverence of the running elk seem somehow mute in comparison to this benediction. But there need not be a contradiction in that.

I am including in the notes (note #1) a poem that I wrote in that monastery. It describes the experience of the ineffable that so impresses me and that justifies patience with all the difficult disciplines of this history.1 I am constantly being reminded of the value to be found personally, artistically, or spiritually in emptiness. This is always disconcerting, yet is good preparation as I began to study Tai Chi and the way of the warrior.

It became clear eventually that this monastic segment of my life was concluded and I commenced again on pilgrimage. By then I had been instructed about the religious practice of pilgrimage both in the Occident and the Orient. As I look back on it, I was not ready for monastic life, a life-long enclosure. But who could have imagined where all this would lead? What I am telling here is the beginning.

I had at this time my first experience of martial Christianity. I was just home from the monastery. I was exhausted. I was at my parents’ home in the country north of L.A. Asleep on the den couch. They had gone out to dinner. Someone knocks on the front room sliding glass door. I am startled out of a deep sleep. Few strangers make it up the steep, precarious road to this hilltop house. I jump up and go to the door. I say, “how can I help you?” Then, having jumped up too fast, I faint, falling over backward, I hit my head on a sharp corner of our rock fireplace. I am unconscious and bleeding. The young man at the door breaks in and helps me up and to the den couch as I regain consciousness. He calls my brother at my instruction. My brother comes out and as they are helping me down around the path and walls that surround our house and lead to the parking area, my mother comes up around the corner and sees me, my bloodied head and bloodied white T-shirt, in the grasp of this young stranger. I calm her ferocious look, “no, he helped me.” As they take me to the car on the way to the hospital, I see this young man’s motorcycle that had a hand gun strapped to the seat and a bumper sticker on the gas tank, announcing that “Jesus is Lord.” He had only stopped for directions to the shooting range. It struck me as a strange conclusion to my monastic career.

In between monasteries and following pilgrimage, I had a studio on Wilshire Boulevard in L.A. I took a job caring for a quadriplegic artist who had just suffered a radical worsening of his condition. I lived with him for a year in his studio on the Boardwalk in Venice Beach, California.2 During this time I met a man who taught me about healing energies. He had a Ph.D. in Physiology and a Ph.D. in Psychology from the University of Texas. He had learned about the energies from well-known psychic healers and Asian practitioners of various traditional healing and spiritual arts. I became obsessed with learning about the “energies.” Psychic energies, Prana and Kundalini in Sanskrit, Chi or Qi in far east Asia. Tsa in Tibetan.

Are the energies the meeting ground of spirit and matter? I will operate as if they are. If it isn’t, then, a priest’s involvement here is like a priest being a doctor, or scientist, or artist. If it is the locus for created and uncreated being, then it is the place of a Christian priest as a specialized mediator of divine grace in the world. Here, I believe, is the means and substance of all form and experience.3

At the end of that employment, while I was visiting my parents again at their ranch north of L.A. I felt the desire to meditate in the Eastern ‘lotus’ style which was not at all consistent then with my orthodox Christian practice. At that time, I was very, very orthodox, perhaps as the result of the recent institutional rejection. (Or perhaps because I had experienced something unusual and real in the monastery and on the road, so excellent that I didn’t want to let go of it.) Nonetheless, in this instance, I meditated Zen style. A number of images, entities, came to mind. But I knew they were not the object of this meditation. Then, I visualized a vastly Great Old Man who stood in a tall imaginary portal in the 18 foot high wall of my room in the Venice studio. He merely gazed at me. He became the guide and the guardian for the progress of this spiritual adventure. Eventually, he showed me the heart of the problem in this story that must be resolved. Though, it took several years for me to realize the significance and desperation of what he showed me.4 (This notes C.G. Jung re the archetype of the Great Old Man.)

I left soon after on pilgrimage, conscious that I was now on a pilgrimage with a specific intent. What that intent was remained veiled behind intuition and symbolic vision. I went first to monasteries in Utah, and New Mexico, then the Appalachian Trail in Vermont in the Fall, then Manhattan…

…the leaves fall glorious dead, blood, magenta red… mother of pearl sky above gentle, clattering, blood-red leaves; mother of pearl sky speechless in magnanimous largess; as I wait, decadence dies, fresh blooms open sky-wide, IN THE IN-BETWEEN, oh yes, between feast and fast, I wait for that last vision that lasts– or at least what to do while I’m here.

So, in Central Park, trees no longer grow green, rather gray before jagged horizon, beneath movements of clouds blown sky high against crystal blue; so, in Central Park, on my way by, the woods fill with damp-trodden leaves, bruise red, glorious dead upon the damp ground, fecund fragrance reaches with hands to caress; it’s time, it’s time, to set time on the shelf, to set sail in wagons drawn by the wind…

Then Texas. Another terrible “emptiness”! On a lonely crossroads in Texas, it occurs to me, that I have a task in the culture of our times, rather than in the path of renunciation and monastic withdrawal.5 What such a task would be was still not apparent. (Oh, that fecund void!) But I knew that it has something to do with art, mysticism, power, and politics. It had something to do with the mural that I was to paint on the back wall of that Catholic church in Santa Ana, California. [Take Note.] This was the mural that received so much publicity at the height of the Yemen Experiment (to be described soon enough). Is it only more disasters that would be triggered by this Icon…?

Soon after having this prescient realization at that Texas crossroads, I was picked up by an old man driving an old pick-up truck with an old camper, pulling an old trailer. He was into extreme fasting and God and the Bible. Not a bad fellow at all. Radical really. We explored together some isolated border towns in the southern mountains of Texas and Mexico. Then I felt compulsion to rush home. The pilgrimage was over. I needed to be in California for…?

My parents picked me up at the desert home of a friend east of L.A. As we left that place, driving back onto the main highway, a golden eagle landed on a power pole in front of us. My dad stopped the car. An eagle was a rare sight there. It looked at us. We watched it. Then it flew off to the west in the darkening but still splendid twilight.

A couple of weeks later, some confusing events- too complicated to explain here, led me to seriously consider Diocesan Catholic Priesthood and the seminary. At that time, arrangements were made for me to visit St. John’s Seminary in Camarillo, California. That was the last place I thought I would ever end up. My parents drove me there. When we arrived, the only parking place was right in front of a large statue of St. John the Evangelist. All three of us focused at the same moment on the larger than life statue of an eagle cut in the marble next to the statue of a great saint. We were all immediately struck by this coincidence. It seemed fated at that moment that I follow this path. Though I continued to resist for many months, I did finally enter the seminary, Fall 1979.

89 [36.] Theotokos Oil on Canvas 5.5′ x 3′ 1977

(Mother of God) After adjusting to the powerful impact that Christian Icons had on me in the monastery, after completing a sculpture commission for the monastery on this same theme,”Theotokos,” and after spending nine months in a Trappist monastery in preparation, I painted this painting. Because this process is similar to the process and intentions of icon makers, I considered this painting to be a ‘modern icon.’ However, by then I had already read that Egyptian Funerary Painting such as the mummy portraits from Fayum, Egypt, themselves influenced 2000 years ago by Greek and Roman painting, were at the root of the development of Christian Icons. I found these funerary portraits entrancing in their unencumbered liveliness, their frontal centrality, and stillness. They gaze from the ‘other world of peace’ into our ‘activity.’ Even at that, this painting remains within the range of Abstract Expressionist tenets as well as Catholic theology.

[Brackets around art numbers indicate 2010 UCB/ECAI Nepsis Art Catalog count.]